We know that Catholic inner exile Theodor Haecker spoke to members of the White Rose from his works on at least four occasions — and that his words spoke to them with a particular intellectual appeal. The dynamic eschatological account of history, evil, and the grandeur of human freedom that echoes in the White Rose leaflets, letters, and private journals suggests that this sixty-three-year-old philosopher had found receptive readers among these restless young adults.

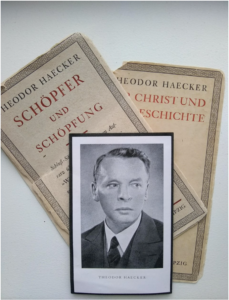

On a sleety Thursday afternoon in early February 1943, members of the White Rose and their wider circle of acquaintances convened to hear Catholic philosopher and inner exile Theodor Haecker read from his book Schöpfer und Schöpfung (Creator and Creation) (1934). They met at Manfred Eickemeyer’s studio, with the White Rose’s duplicating machine likely somewhere in the building. In attendance were about thirty people, some young and others not so young: students, booksellers, artists, intellectuals. Only the night before Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, and Willi Graf had been graffitiing streets around Munich University with slogans like “Down with Hitler” and “Freedom.”

Freedom was the main topic of Haecker’s lecture; and Haecker was insisting upon his own freedom of speech that night, given that he’d been prohibited from public speaking since 1935. Just two weeks later, Hans and Sophie Scholl would be caught as they distributed the sixth White Rose leaflet in the hallways of the university. Risk taking seems to have been a shared tendency in these days, when Allied bombs were falling from the air and Germans were processing the reality of defeat at Stalingrad.

My research for the White Rose Symposium has circled around this one night, who was at Haecker’s reading, why they were there, and what was read. I’m convinced that we need new ways to understand how, why, and what it was about mentors like Haecker and his friend Karl Muth that “spoke to” the intellectual and religious restlessness of the White Rose students. We need to allow these forgotten figures to “speak to us,” even when we run into obstacles along the horizon of our own scholarly expectations and interdisciplinary expertise. We need to call in the help of the best research into the hermeneutics of inner exile (Rotermund & Rotermund, Dodd, Klapper), so that we can connect the dots between all the available sources: works published during the Third Reich, private letters and journals preserved after the war, official documents, and memoirs that offer their own takes on what ignited these young adults.

Did Haecker know about the White Rose’s leafleting campaign at the time? Nothing suggests that he did, but it’s hard to imagine him stumbling upon any of the first four leaflets without noting their curious proximity to his philosophical lexis and his eschatological critique of National Socialism. He’d been developing this critique in both his published inner-exile writings (where it twitches beneath the surface) and in his unpublished journals (where he names it without restraint). We know he’d read to the White Rose from these journals and that their conversations had included explicit reference to Hitler and his regime.

My paper includes a profile of Haecker’s idiosyncratic anti-Nazism, which first appeared in print in 1923, several months before the Beer Hall Putsch. The essay he would read to the White Rose in February 1943 had been written in 1933, during months when the gestapo was investigating him because of a 1932 essay where he’d vilified the swastika as the twisted, spinning cross, the symbol of the diabolical swindle duping of Germany.

With that in the background, Haecker wrote Creator and Creation to address the kind of big questions that human beings tend to ask in dark times: Why did God create the world as it is? Why does He let evil happen? What role can the individual human person play in the worst of times when tragedy is everywhere? The finely wrought essay crescendos toward a celebration of the freedoms that rest beyond the grasp of the state, namely, the freedom that is human conscience. But Haecker goes beyond even the free, ethical scope of personal conscience to propose a higher, sovereign freedom exemplified in the lives of saints and martyrs. This sovereign freedom is the divine gift of willed participation in the creator’s “free act of a holy will to love, to give, and to communicate Himself.” What does this mean for human action in the world? It’s an agapic mandate, ama et fac quod vis, a phrase that Haecker borrows from St. Augustine: “Love and do as you will!”

What Haecker read on February 4 is ultimately a proposal that the possibilities of human freedom extend beyond freedom from oppression and even beyond freedom to build a better life. He’s describing a radical freedom in love, a freedom to which not even death poses a limit. Was this the kind of freedom that Hans Scholl meant when he yelled those last words at the guillotine? “Es lebe die Freiheit!”.

Dr. Helena M. Tomko is associate professor of literature in the Department of Humanities at Villanova University in Philadelphia. She studies the Catholic presence in early twentieth-century German literature and culture, in particular writers associated with the “inner exile” during the Third Reich. She completed her doctoral studies at St. John’s College, Oxford, having studied for her undergraduate degree at Bristol University. Her book, Sacramental Realism: Gertrud von le Fort and German Catholic Literature in the Weimar Republic and Third Reich, was published in 2007. Her recent articles have appeared in venues including German Life and Letters, Oxford German Studies, New German Critique, and The German Quarterly.