By Ro Crawford and Alexandra Lloyd

For the fourth year of the White Rose Project (2021-2022), we wanted to explore processes of translation beyond the typical transfer from a source language to a target language, especially since this would open up the White Rose Project to students with no knowledge of German for the first time. These ‘creative translations’ by students at the University of Oxford are imaginative responses to, and interpretations of, real events and people as encountered in interviews and primary sources. They explore the courage and conviction of students who, eighty years ago in Germany, stood up to fascism and used the written word to resist. The translations were developed through a series of workshops and seminars from January to March 2022.

The creative translations included here illustrate the ways we mediate messages we find important across a variety of genres, forms, and media. Whilst we did not want to replace the work of the White Rose or diminish its historical significance, the project has always invited its participants to think about the differences between the original context of the group, their pamphlets, and our situation today, and these creative translations can be seen as reflections on that distance.

Alexander Kahn | Oil on Canvas

Depicted are four members of the White Rose, gathered around a draft of a pamphlet. Also visible are the shadows of Alex Schmorell and Kurt Huber. Though the six members of the White Rose movement are present, this is not a painting of a real moment; it is a symbol.

This is painted with oil, mostly reds and browns – entirely without blue. Detail is conveyed through colour and form. The room is dimly lit. No lights are switched on; the only dim light that comes into the room are from windows outside of the frame. A thin crack of sunlight pierces the darkness of the room from between the shutters of one; from another, a pink glow comes through, as if passing through a red curtain.

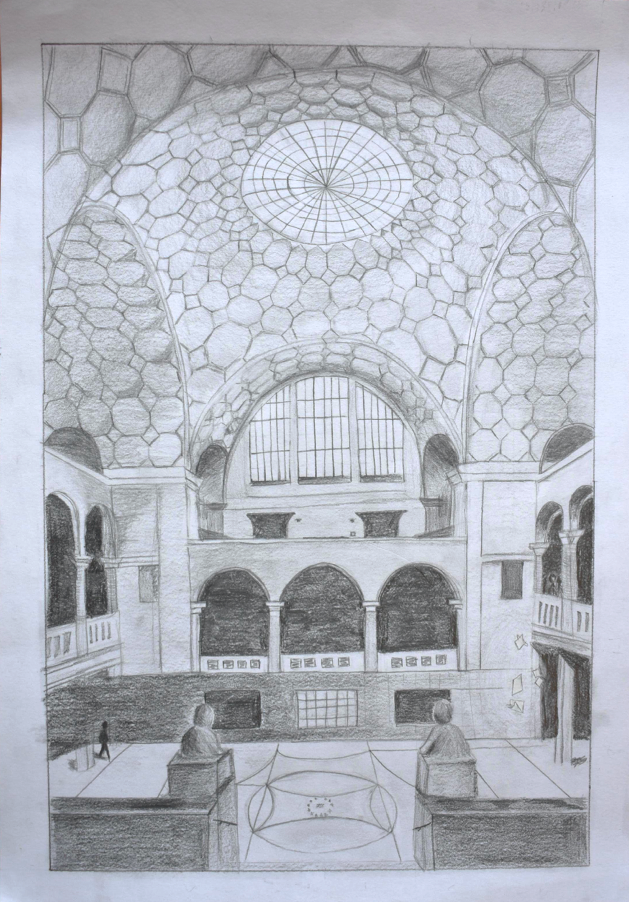

Lydia Ludlow | Lichthof

My piece represents the famous scene in which the pamphlets were thrown off the balcony in the atrium of Munich University. It is a heart-stopping moment, which epitomises the bravery – and perhaps the naïveté – of the White Rose members. I wanted to focus on the moment just after the pamphlets had begun to fall, but before they landed and were discovered, which would lead to the group’s downfall. There is such hope and potential in this moment: I wanted to freeze the last moment before the fate of the group became inevitable. I think a lot of the power of this moment comes from the words in the pamphlet: words full of radical possibility, but also words that were enough to condemn their authors to death.

I found the direct appeal this pamphlet makes to its authors’ fellow students particularly moving. The emphasis on ‘Freiheit’ and ‘Ehre’ and the strength of their language of condemnation is striking. Therefore, I wanted in the piece to pay attention to the words of the pamphlet, rather than the personalities of the group. The only people in the scene hide in the shadows: you can just make out a couple of figures on the balcony on the right, and in the bottom right-hand corner you can see the janitor lurking, foreshadowing the inevitable discovery of the pamphlets. I chose not to include captions, so all the words present in my comic are taken directly from the sixth pamphlet, and I have left them in German. I hope this gives the pamphlet a chance to speak for itself. However, in the final frame I have highlighted some of the words and phrases that I found most striking, so there is certainly an element of interpretation and mediation to the presentation of the words.

I was inspired to try and produce a comic strip after the workshop with Amey Zhang. The style of drawing is also inspired by the graphic novels of Brian Selznick, which I love. His novels always have a strong sense of place, often feeling cinematic. He also often uses changes of scale in a similar way to how I have, in order to ‘zoom in’ on a subject.

Ursy Reynolds | Scriptorium

I first learned about ‘scriptoriums’ from Mary Wellesley’s brilliant book Hidden Hands: The Lives of Manuscripts and their Makers. Wellesley describes the collaborative nature of these medieval, usually monastic, writing rooms, where stories were chronicled, compiled, and decorated by a group of like- minded individuals. A certain overlap with the White Rose group emerged particularly for me when I learned about the influence of Kurt Huber’s reading evenings. These events stimulated intellectual discussion and brought together this resistance group, within the context of another institution of learning: not a monastery, but a university.

My poetic response attempts to encapsulate that overlap of common intellect, a desire to both preserve beliefs and send out a persuasive message. In the poem, I tried to include an abundance of almost obtrusive grammatic devices in the form of colons and brackets to reinforce the ardour of word-crafting, the complexity of communicating by writing. The reference to ‘a forever narrative’ was a suggestion of another similarity between medieval manuscripts and the White Rose papers, whereby both had the aim of leaving a didactic legacy for both present and future generations. I wanted also to bring the theme of printing into my poem, with ‘(though a single sheet they had to be)’. Just as medieval manuscript makers had complex guidelines regarding page spacing and line work, and were restricted by the tools of their era, the White Rose group were limited by their resources, time, required secrecy, and ‘pamphlet’ method of delivery.

Certainly the parallels I have drawn out are not the only ones, nor would it be correct to suggest the scriptorium and the White Rose existed in social circumstances akin to one another. However, my interest was piqued by the remarkable affinities between these two groups, centuries apart in the German past, but strangely close in their lives’ dependence on the written word.